Here is his description of the two models:

Regular readers know that under the Japanese model losses on the excesses in the financial system are only recognized as banks generate the capital to absorb them. This is good for banks because the model involves hiding their true condition and pursuing policies designed to boost bank earnings. It is bad for the economy because it distorts asset prices and access to capital (for proof, look at the performance of Japan's economy).Richard points to recent events in Iceland as another successful application of Sweden's model. There, the country's banks forgave loans equivalent to 13% of gross domestic product, according to a Bloomberg article Richard cites. The equivalent in the United States would be about $1.95 trillion of mortgage debt writedowns. Icelandic banks agreed to forgive all mortgage debt over 110% of a home's value.

The alternative is a Swedish model that is bad for banks and good for the economy. It is bad for banks because they are required to recognize the losses on the excesses in the financial system today. It is good for the economy because it avoids the distortion in asset prices and access to funding associated with hiding the losses under the Japanese model (for proof, look at the performance of Sweden's economy).

Not only that, Bloomberg relates a development that would meet, I believe, with the approval of Tea Party members and Occupy protesters alike: Bankers were held personally liable for crashing the country's economy. The CEO's of the country's three largest banks are among 200 who are facing criminal charges, and a special prosecutor expects up to 90 more indictments. The contrast with the United States could not be more obvious.

While Iceland is a tiny country with a population of only 317,000 and a $13 billion GDP, Trust Your Instincts is not the only blog paying attention to it. As Paul Krugman wrote yesterday, "I think I may have been one of the first commentators with a wide audience to point out how relatively well Iceland was doing." What he didn't mention, though his commentator "iInfoliner" did, is that the credit rating agency Fitch upgraded Iceland's debt to investment grade last week. Moreover, according to the Business Week story, the country can now borrow in U.S. dollars at a mere 4.77%. Compare this to Greece at 35.98% and Portugal at 12.77%; even Spain and Italy are a little over 5% (the FT link has no rates listed for Ireland).

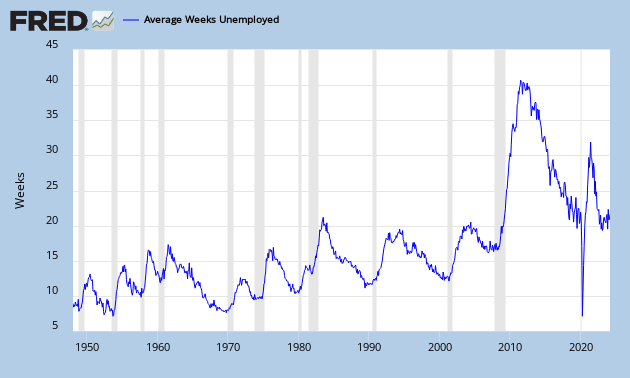

The moral of the story is that a different approach to dealing with the banks is necessary, both to restore the U.S. economy but to prosecute financiers who broke the law. As it stands, bankers have gotten off scot-free while the country's economic growth has been largely anemic. While the job market has shown a few flickers of life recently, the country needs millions of jobs just to get back where it was before the crash, which actually wasn't all that good a situation for the middle class to begin with.

It could be worse, I suppose. As Richard says, Japan's economy remains smaller than 15 years ago. But Ben Bernanke was rumored to have learned the lessons of the Japanese experience. Whatever happened to that guy?